Choosing program material for subjective evaluation of audio components is challenging because the acoustic characteristics and qualities of the recordings themselves can bias and influence the results [1], [2]. The programs must be sensitive to and reveal artefacts present in the devices under test, otherwise an invalid null result may occur (type II error). Ideally, the programs should be well recorded and not contain artefacts that may be inadvertently attributed to the headphone or loudspeaker. For example, an accurate headphone may be misperceived as sounding too bright or too full if the recorded program contains an excessive amount of boosted high or low frequency information. These so-called “circle of confusion” errors [3] caused by a lack of meaningful loudspeaker-headphone standards make it difficult to choose neutral programs that don’t bias listening tests.

It would be ideal if there existed a list of recommended programs that meet all the above criteria, or an objective method for selecting the best programs. Unfortunately, the current listening test standards provide neither solution:

“...There is no universally suitable programme material that can be used to assess all systems under all conditions. Accordingly, critical programme material must be sought explicitly for each system to be tested in each experiment. The search for suitable material is usually time-consuming; however, unless truly critical material is found for each system, experiments will fail to reveal differences among systems and will be inconclusive. A small group of expert listeners should select test items out of a larger selection of possible candidates.” [2].

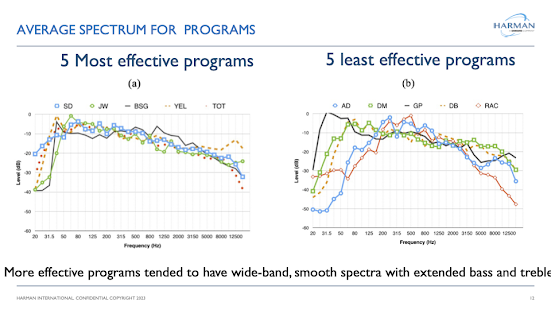

Some insight into selecting effective programs for headphone evaluation may be gained from previous loudspeaker research where the spectral attributes are best evaluated using programs containing wideband, continuous spectrally dense signals. Low and medium Q resonances in loudspeakers are most easily detected using wide band continuous signals, whereas higher Q resonances are most sensitive to impulsive, discontinuous signals [4], [5]. The performance of listeners in categorizing spectral distortions added to headphones increases as the power spectral density of the program increases [6]. While we don’t recommend evaluating headphones using pink noise, there may be benefits in using music tracks that have broadband continuous signals mixed with some impulsive transient sounds as well. For judging the spatial and distortion attributes of headphones a different type of program may be required.

A listener’s familiarity with the program and their affection for it from a musical or emotional perspective may also influence their sound quality judgements. Naïve listeners and audiophiles often criticize formal listening tests because they’re unfamiliar with the programs, or they dislike them. Whether this affects their performance as listeners is not well understood. ITU-R BS 1116 recommends: “the artistic or intellectual content of a programme sequence should be neither so attractive nor so disagreeable or wearisome that the subject is distracted from focusing on the detection of impairments.” [1].

A listening experiment was designed to address some of the above questions: 1) which programs are most effective at producing sensitive and reliable sound quality ratings of headphones 2) to what extent does familiarity with the program play a role and 3) are there physical properties of the program that can help predict their effectiveness in evaluating programs? A post-test survey was also administered to determine whether the listeners’ music preferences for certain programs and other factors influenced their performance and headphone ratings.

We published an AES preprint in 2017 that describes and summarizes the results of the experiments which can be found here (https://www.aes.org/e-lib/browse.cfm?elib=18654) .

I've also created a PPT presentation that summarizes the experiments and results below.

References

[1] International Telecommunications Union, ITU-R BS 1116-3, “Methods for the subjective assessment of small impairments in audio systems,” http://www.itu.int/rec/R- REC-BS.1116-3-201502-I/en, February 2015.

[2] International Telecommunications Union, ITU-R BS 1534-3, “Methods for the subjective assessment of intermediate impairments in audio systems,” (October 2015).

[3] Toole, Floyd, The Acoustics and Psychoacoustics of Loudspeakers and Rooms, Focal Press, first edition 2008.

[4] Toole, Floyd E., and Olive, Sean E. “The Modification of Resonances: Perception and Measurement,” AES Volume 36 Issue 3 pp. 122-142, (March 1988).

[5] Olive, Sean E., Schuck, Peter L., Ryan, James G., Sally, Sharon L., Bonneville, Marc. “The Detection Thresholds of Resonances at Low Frequencies,” J. AES Volume 45 Issue 3 pp. 116-128, (March 1997).

[6] Olive, Sean. E, “A Method for Training Listeners and Selecting Program Material for Listening Tests,” presented at the 97th Audio Eng. Soc. Convention, preprint 9893, November 1994.